Get Out The Vote: 1915 and Earlier

Women’s and African-Americans suffrage.

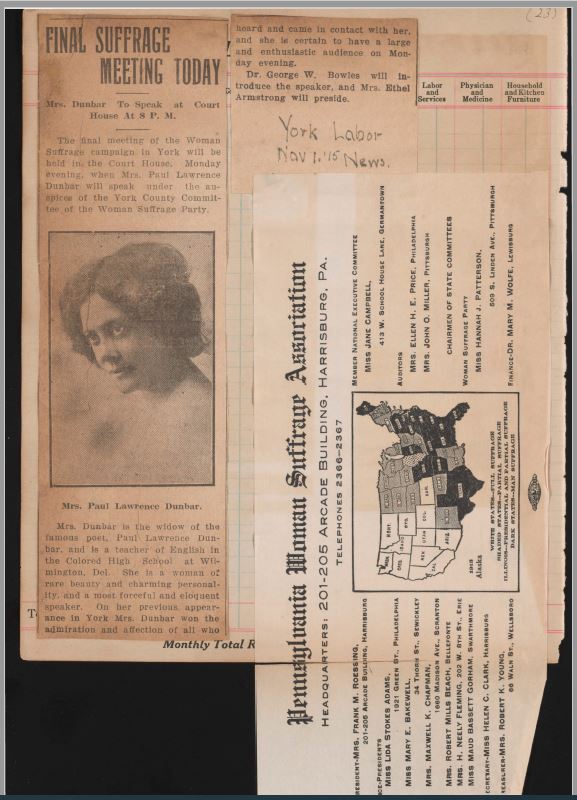

Alice Dunbar-Nelson saved this classic suffrage swag, a map showing the growth of women’s right to vote. Like many scrapbook makers, Dunbar-Nelson reused an old book or ledger. Hers was a household accounts book, probably never used. When scrapbook makers pasted over other books, they demonstrated that they valued one text over the other: in this case, suffrage work over close attention to individual housekeeping.

November 2, 2020

Since retiring from teaching at NJCU, I miss handing out voter registration forms in class, and assignments that help students think about the importance of voting. This year, I wondered what new channels I could find to get out the message to VOTE.

I’d heard of great ways social media was tapped for this — discussing voting on the dating app Tindr, for example. I’m happily married, so wasn’t going that route, but I do have a blog and Facebook page based on my research for my 2013 book, Writing with Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance. Aha! I decided to post about how scrapbook makers documented voting – women struggling for the right to vote, African Americans fighting white attempts to suppress their votes. The right to vote is precious and was hard-won.

Scrapbook makers were often passionate about voting. They didn’t paste down selfies wearing “I voted” pins, but they showed it other ways. White activists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Lillie Devereux Blake in the 70-year fight for women’s right to vote, used scrapbooks of newspaper clippings to document their campaigns, review the publicity they’d gotten, save material for speeches, and strategize about how to fight effectively. Some Black men who made massive collections of clippings after the Civil War, on African American life and the changing political situation, used their scrapbooks to save evidence when white politicians schemed to keep them from voting. Years later they might bring out that evidence, to shine a bright light on what these politicians had done in dark corners.

Scrapbooks save the stories of people like Alice Dunbar-Nelson, an African American writer, teacher, poet, playwright, accomplished public speaker, and an anti-lynching activist of enormous energy and vision. But her suffrage work is missing from white-centered women’s rights histories. It’s only because she kept a scrapbook documenting her speaking tour for a Pennsylvania suffrage campaign in 1915, that we know of her role in winning women the right to vote. Newspapers wrote down parts of her speeches.

Dunbar-Nelson took a break from teaching to tour Pennsylvania in a suffrage campaign in fall 1915. Her speeches weren’t the usual white suffrage message. She focused on what Black women’s votes could do for the Black community. Of course, only men were allowed to weigh in on whether women could ever cast a ballot, so she had to persuade men to support women’s right to vote.

Although white suffragists often spoke as though women did not work for wages, Alice Dunbar-Nelson explained repeatedly that Black women’s work outside the home benefited the Black community as a whole. She argued to a Black audience, “Our women have literally built up [our] race in domestic service, which keeps them out of their home all day long; that means that the majority of our women are out of their homes every day helping the men to accumulate [resources]. If we are good enough to help in all this, it looks as if we are good enough to cast a vote.” When anti-suffragists claimed that politics was too “dirty” for women, Dunbar-Nelson responded, “Politics is the only dirt we don’t get into at present.”

Black women’s votes could help bring the Black community better housing conditions, she argued. Suffrage was not just about the vote itself, but what African American women could change with the vote.

Looking at these scrapbooks and the careful, ceaseless effort they document reminds me how precious their makers considered the right to vote. I’ve tried to share that history on my blog. Please pass the word! Vote on!

will guzman • Nov 2, 2020 at 11:19 pm

Great article. Alice Dunbar-Nelson led an amazing life, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/dunbar-nelson-alice-ruth-moore-1875-1935/