By Katherine Guest—

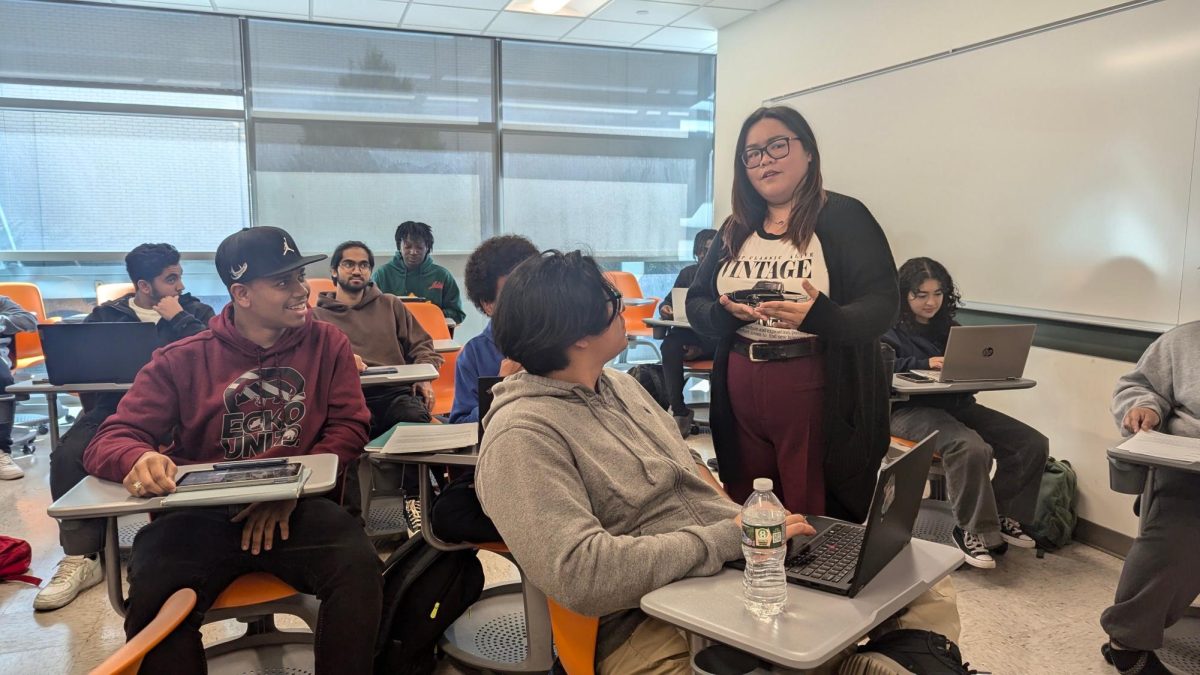

As a Mexican-American citizen and human rights activist, Enrique Morones, stepped up to the lectern, the NJCU community applauded in approval on the autumn afternoon of October 16, 2012.

“I’m glad to be here at the University,” said Morones, “I’ve been also impressed with the diversity of the campus. I see a lot of people of my race and that’s the human race, so thank you.”

Morones founded the non-partisan group Boarder Angels after he heard the story of the canyon dwellers that inhabited East Los Angeles, CA, in 1986. (East Los Angeles’ population consists of Korean, Mexican/Hispanic, African American and Caucasian communities). The canyon dwellers were migrants who worked on the strawberry fields.

“A woman from El Salvador told me about the mistreatment of migrants. I was heartbroken to hear that people were living in a canyon in East Los Angeles, a rich neighborhood, because there weren’t any affordable housing.” Morones continued, “This was the moment when the spark lit the flame inside of me.”

Boarder Angels sends volunteers, who are financed by donations and t-shirt consumptions. They are stationed primarily along the coast of San Diego and near deserts. The advocates’ main goals are to provide food and blankets for migrants.

Morones explained that “indigenous people have rights too.” Migrants come to this country for “economic opportunity. They want to put food on the table for their family. That’s it.”

In October 1994, about 10,000 people died because of Operation Gatekeeper, a blockade that caused the migration of Mexicans much more difficult. Instead of crossing a terrain of short distance, immigrants now had the option of climbing a steep mountain with brutal, Eskimo weather or crawling through the dehydrating sandbanks of the desert. Immigrants who dared to swim across the All-American Canal drowned because of exhaustion. The canal was wider than the eye could grasp.

Morones is the leader of anti-Operation Gatekeeper. When finding out about the US building a wall from the Pacific Ocean to the southeast of San Diego, the second largest city in California, he shifted his focus from just the canyons, to the desert as well.

“People want to do the right thing, but some don’t know how. I’m going to do something,” he said.

Morones quoted Martin Luther King saying, “You have to let people know: injustice here is injustice everywhere.”

“The U.S. is one of the most powerful nations in the world so they should set an example for other countries by practicing what they preach.”

“People are not only dying by trying to cross the border, but also within the country,” he said.

Morones told a story of an Ecuadorian, in Long Island, NY, who was kicked to death by seven misguided souls.

On April 1, 2005, the minutemen were formed to patrol the border of illegal immigrants. Morones called them “a disease.” The organization claimed the minutemen were “keeping the community safe.” From then on Morones knew the movement was “definitely racist.”

“One of the racial problems immigrants deal with is the language people use. People call them names like WOPs (without papers) or illegal aliens, there are 11 million undocumented people in the US and one of them, for example, is Arnold Schwarzenegger.”

There are many myths that burden undocumented immigrants take jobs, don’t pay taxes, and cause increased crime rates.

He defends these myths by stating that migrants are in a completely different economic sector. Immigrants pay income tax, local tax, federal tax, etc. Lastly, undocumented migrants usually do not want to participate in crime activity because of the border crossing difficulty.

“Get in line, but there is no line. It’s a myth.”

Morones advocated for several different organizations and movements. Morones was part of the “Trail of Tears,” which was a 125 mile walk that took about a week to finish. On August 12, he joined the Caravan of Peace, an organization that attempts to stop money laundering amongst both sides of the Mexican and US border. Border Angels’ goal is to work with a variety of groups and take down Mexican hate groups in a peaceful manner by educating and forming different coalitions.

“I’ve been to several other countries such as Europe, Asia, South America, and Central America because people who are trying to migrate don’t go to the United States first, they go to other countries,” he said.

Morones is working toward a balanced immigration reform. He is advocating for migrants to learn the English language, pay something to the government, and form a non-mythical line. It’s going to take time for a bill to pass through the Senate. He suggested helping countries undocumented immigrants came from so the people could develop a stronger economic system.

“Create a system where people can get in line like Elise Island at one point,” he said.

Morones NJCU could even start a Border Angels Chapter on campus.

“I think that it’s a very important topic because the community of the University is greatly populated with diverse students,” said Catherine Raissiguier, Women’s and Gender Studies Professor. “Some that know people with similar struggles Enrique Morones [described] during his speech. I think the talk had a particular resonance with this place.

“It seemed like the students were focused and moved by the talk. For example, the one young man [an NJCU student] who spoke during the Q&A portion of the segment portrayed emotion,” said Professor Raissiguier.

One of the students of NJCU spoke about his friend who is an immigrant and recently crossed the U.S. border from Mexico illegally. He also spoke about his visa being expired after coming here from El Salvador 15 years ago.

“I think he did an amazing job. He mentioned so many things. I was actually well educated because he spoke from the heart,” said Eman Khalil, 24, woman and gender studies major from Cliffside Park.

Lawrence M. Ladutke, Legislative Coordinator of Research Development, said “[Morones was] very good. This is an issue I personally volunteer [in] with Amnesty International USA. I work trying to influence legislation.” More specifically, “There are not many options for women and migrants, either death from trying to enter the U.S. or death in their own country.”