A Tale of Two Urbans

June 8, 2016

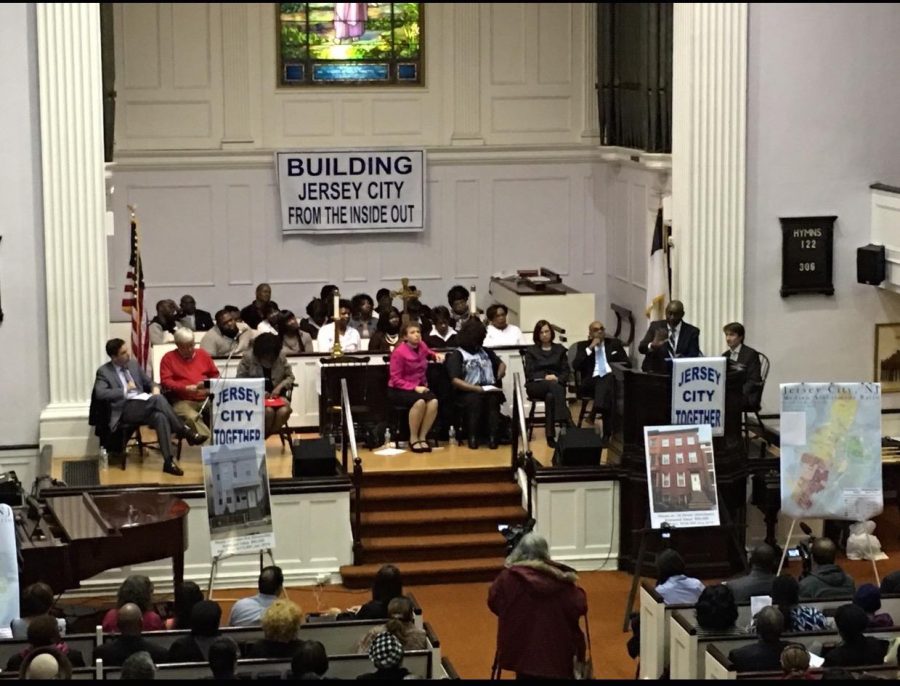

The activists stood on the right side of the altar, the politicians on the left. The doors of the church opened to an intense community meeting between religious leaders, citizens and politicians. From the audience it seemed more like a boxing match than a town hall gathering. The religious leaders came out swinging with facts, sometimes forcing the politicians to retreat to the ropes.

Jersey City Together, a coalition of more than 30 multi-faith groups and community organizations, had called for the meeting. Almost 900 people packed the pews, filling the church from the altar all the way to the balconies. Their plan, to “Build Jersey City from the Inside Out” focuses on three main concerns: dislocation, education, safety and policing.

After months of meeting and disagreeing over the need to use tax funds to remedy these concerns, the coalition was finally able to hold the public meeting with Jersey City Mayor Steve Fulop and other officials that night.

Reverend Alonzo Perry, of New Hope Baptist Church, firmly stood in front of the cheering crowd, insisting that the racial and socioeconomic divide “is beginning to look like a ‘Tale of Two Cities’.” A sentiment preached often on the unevenness created at the hands of gentrification. A strategy developed to end poverty has, in many ways, propelled it, argued Pastor Perry.

Jersey City Together voiced that most residents’ problems with gentrification stem from the decision to cater to developers and the downtown area, instead of the community. The Bergen-Lafayette and Greenville are (Wards A and F), in particular they said, are flooded with issues ranging from unsafe streets, to a failing public school system.

The coalition members continued, voicing concerns about the dislocation of residents. They explain that the homeless were forced to move due to the horrendous conditions of The Starlight Motel, one of the last existing shelters in Jersey City. Other residents were forced to move after low-income housing was demolished for luxury housing or due to the ever-climbing rent and taxes.

The coalition argued that while the downtown area has an abundance of police protection and presence, the streets of Bergen-Lafayette and Greenville are becoming unsafe due to un-working CCTVs (cameras) and uneven distribution of on-duty police.

They also critiqued that while there is a decline of job opportunity there is an increase of taxes in poorer neighborhoods; one of the main concerns of that evening and the most apparent effects of gentrification.

Terrence McDonald, a reporter for “The Jersey Journal” said, “Many taxpayers in the communities where there aren’t tax breaks, such as Bergen-Lafayette or Greenville, feel they are shouldering the tax burden for the residents of skyscrapers in Downtown and Journal Square that receive tax breaks. The city argues that the skyscrapers wouldn’t exist were it not for tax breaks, and that the city would lose the revenue it receives for the developments if they weren’t built at all.”

“When developers receive tax breaks, they pay a Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILOT) to the city instead, and the city keeps most of that money. If they were to pay conventional taxes, they city would split that revenue with the county and the school system. So as each tax-abated property goes up, the school district loses out on more and more tax revenue,” said McDonald.

“Schools lose out the most,” said McDonald.

Middle School Teacher John Flora, stated that, “Twenty-two percent of the money from a tax abatement is diverted away from the school [system]. We need more money instead of less money.”

“The issue we have with the district is not having any accountability for the after school program. Presently, according to OPRA (open public record act) there are no after school programs funded by the district,” said Flora.

Reverend Willie Keaton stated, “When it’s time for funding for afterschool there’s no funding—while schools in urban neighborhoods are crumbling the prisons are successful.”

Reverend Keaton, standing to the right of the podium, said, “if we are going to build Jersey City from the inside out that means we will start with children and invest in schools.”

Jersey City School Superintendent Marcia Lyles was called to the left side of the alter and asked if she would state publicly that she would commit to $2 million for a quality program to get 1,500 more students involved in the afterschool program at three to five of the worst performing schools.

Lyles agreed to the proposal, and stated, “We understand the urgency to forge the future.”

Max Herman, Associate Professor of Sociology at NJCU, also attributes the uneven development in Jersey City “to be a factor in the problem.”

Herman explained that generally with gentrification, “Most of the money is put into developing downtown. They are closing neighborhood based schools instead of putting resources into making them better.”

The History of Gentrification in Jersey City

Dr. Donal Malone, associate professor at St. Peter’s College, sheds light on the complexities of the long and tangled history of Jersey City’s battle with gentrification. Malone’s extensive research finds elected officials operating in the interest of developers more often than residents.

In his article, “Neoliberal Governance in Jersey City,” he stated, “From the 1950’s to the 1980’s, Jersey City, like many other cities, was in a period of decline with the loss of its manufacturing base and the flight of capital, business, and much of the middle class to the suburbs and elsewhere.”

As a result “of a shrinking tax base and declining federal and state funding, Jersey City turned to the private sector for investment to revive its economy. It established public-private partnerships with real estate developers and financial service corporations. This was a shift from a managerial to an entrepreneurial style of governing,” Malone continued.

“To attract business partners—Jersey City has engaged in—activities—[such as], governmental officials providing various tax breaks, create economic development corporations, establish urban enterprise zones, grant zoning variances and sell public land and buildings as well as the city itself with branding campaigns,” Malone explained.

Malone continued, stating, “In 1980 Jersey City created the Jersey City Economic Development Corporation (JCED) as it began a new era of public-private partnerships.” It is described as A private 501 (c) (3) non-profit corporation with the support of the Jersey City Administration and Municipal Council, [its mission was to] promote, encourage and assist the industrial, commercial and economic development of the City of Jersey City…creating greater employment opportunities and broadening the base of the tax structure (JCED 2015).

Malone continued, “Subsidies for businesses would be used as incentives for them to invest—In addition, there were state subsidies for businesses relocating to Jersey City (JCED 2008 5). This new entity became the city’s second agency whose mission was to find investors for redevelopment. These semi-public, independent agencies, consisting largely of non-elected officials, made decisions regarding what areas of the city were deemed in need of redevelopment, who the developer would be and how the city would facilitate that process.”

“The first public-private partnership began in 1983 with a $40 million federal urban development grant from the Regan administration, the largest ever at the time. The grant was exceptional since it was a period in which the federal government had withdrawn much of its financial support from cities. Some of the money went for sewers and streets to build Newport, a complex of corporate office and luxury apartment tower as well as hotel, marina, and mall on the city’s waterfront,” said Malone.

“While the growth of financial services and associated industries did not provide many jobs for residents, it created a demand for low wage jobs to serve the professional workers in these industries. The result has been the rise of a two-tiered workforce of low and high wage earners reinforcing class, racial, ethnic and gender divisions in the city. The increase in low wage jobs to serve professional workers has been cited by some local officials as justification for providing subsidies to relocate jobs,” stated Malone.

“Another sign that corporate finance companies and luxury housing may have been competing with factories for urban space was the steeper decline of manufacturing jobs in Jersey City than elsewhere. In 2002, manufacturing jobs were 5 percent of Jersey City’s private sector jobs; 10 percent in Hudson County; 11 percent in New Jersey; 14 percent in the U.S. (UEZ 2005 41),” Malone said.

“While the loss of manufacturing jobs was due mainly to a long-term trend of deindustrialization, local officials reinforced this process in making corporate finance and luxury housing the primary focus of their redevelopment strategy,” explained Malone.

Facing the Crowd

Reverend Perry stood between two mounted pictures. The image to the left showed a house with pale blue vinyl, with shingles covering the exterior of the home. The image to the right revealed a brownstone. One home was located was located in Greeneville on Linden Avenue, the other home was on 1st Street, in downtown Jersey City, said Reverend Perry.

“Both homes have an assessed value of $90,000, [yet], the house on Linden Avenue’s property taxes are $6,000. [While] the house on 1st Street is almost $2,000,” said Reverend Perry.

“How is it that the house on Linden Avenue sold for $170,000 and the house on 1st Street sold for $500,000? Why are the taxes on one house three times more?” asked Reverend Perry, perplexed by the discrepancy of the images.

“This is not political, this is unfair,” stated Reverend Perry.

“People on one side of the city pay more than people on the other side of the city—this is an issue of social justice,” said Perry.

“One side of the city is being over taxed and [the other] side is very developed,” said Perry.

“Stop the rhetoric—all I want is a level playing field,” he urged Mayor Fulop.

Untiring, Reverend Perry continued, rising and sinking, and losing and gaining momentum—his voice carrying the flow of the crowd.

Marching back to the right side of the alter, Reverend Perry faced Mayor Fulop and asked if he would commit to a reevaluation done responsibly and fairly and to fight for money that was ill spent. He ended his speech reminding the mayor that people were losing their homes and that the community wanted strong leadership from the mayor of the entire city.

As Fulop claimed his position on the left side of the alter, he faced the anxious crowd, stating, “The process of reevaluation was started when I took office and I cancelled it because I saw the direction it was already headed in. People would have lost their homes.”

“People are losing their homes now. There’s a crisis in the city,” exclaimed Perry.

Turning to Fulop, he asked, “Will you support a reevaluation of taxes in Jersey City and when?”

Fulop retorted explaining that the courts were still deciding and that he could not give an answer until he knew whether discovering if ill spent money would be retrieved.

As Fulop stepped away from the podium, and Reverend Mona Fitch-Elliot, of St. John’s Lutheran Church, took to the right side of the alter.

She pointed to a picture of a family standing outside of a brownstone home, “We might have a fear of what will happen to people downtown, but it’s already happened downtown,” she said revealing that the image was of her family, who once lived downtown and were displaced.

“Many families suffer. [And] the indigenous have not been involved in any decisions made by corporate giants—and businesses with the interest of Jersey City,” she said.

Reverend Elliot pressed that the people were ready for action, “[To] shed light on what has been hidden. [We] want to be at the table where decisions are being made. [We] want to know about taxes, how the money’s spent and who’s getting it, and the funding of schools.”

“Downtown use to be on Martin Luther King Boulevard,” said founder of The Jersey City Anti-Violence Coalition, Pamela Johnson, but like many gentrified communities, the heart of the city moved to the edge.

According to Malone, after LeFrank was given a 15-year tax abatement “for the shopping mall and tens of millions of dollars in tax breaks from the state of New Jersey to help finance [his] project.” LeFrank also received “$135 million in Federal Housing Administration—to subsidize the construction of 1,500 rental apartments.”

Rich Cohen, director of Jersey City’s department of housing and economic development, said, “… Unfortunately, the wonderful waterfront development is going to be a luxury preserve.”

“He was right,” said Malone.

The transformation of the waterfront development into luxury housing marked a shift in territory. Prior to the development downtown Jersey City was ethnically diverse and economically poorer. Yet, in the climate of change, many people lost their homes.

“The waterfront, as well as nearby neighborhoods, have become affluent enclaves. In allowing luxury housing developers to opt out of on-site affordable housing, local officials set in motion a pattern of housing segregated along class, ethnic and racial lines that has continued to this day,” stated Malone.

“Even in the images, (of the Bayfront development on Route 440), there aren’t people of color. –That’s not their target audience—the target audience is middle class white people,” Herman said.

“Gentrification is a tricky word. It means different things to different people,” says Terrence McDonald, the reporter for “The Jersey Journal.”

“[But] yes, it’s clear that Jersey City has gentrified (or at least portions of it). The Downtown used to be much more racially and ethnically diverse and poorer, and now it’s whiter, with wealthier residents and fancy cafes. Journal Square is on its way. I wouldn’t be surprised if a Starbucks opens up there soon, which is one of the first signs of gentrification,” McDonald continues.

To 25 year old Jersey City resident, Khalil McCloud, gentrification is an overcrowding of minority or poorer areas.

McCloud said, “It makes it worse on us because everyone kicked out of the projects come to live over here. There is an overcrowding, person from other places come up here to do what they were doing. Someone from every gang loses.”

As for growth, McCloud said, “its growth—but who could afford it. People are making $8 an hour. Who could afford $1,500 for two bedrooms? If it’s for the benefit of the people than raise minimum wage because people are living from check to check—[there] are too many liabilities but no assets.”

“Politicians only make promises to get more votes. It’s not just politics, it’s people too—a lady was just shot for nothing—murders happen because people are at the wrong place at the wrong time,” said McCloud.

“That’s how they want it. It’s not a problem until it’s a high profile shooting, or someone important is involved and they blame anyone just to shut people up. All they do is have [police] patrol for a few days to make it look good but they don’t care,” said McCloud.

“It’s never going to change. Hope, you have to give people hope. I used to be young and dumb,” said McCloud.

“[But] who are you going to cry to? I just know how the streets suck you in. You could have great parents [but] it’s all about where you go to school and who you surround yourself with,” said McCloud.

“Someone like me could make a change because I have the power to get people to change. I could tell them to get off of the streets but they have to have somewhere to go to make money.”

“People are killing to survive—to make money,” said McCloud.

“[But] it’s all a scam—it’s all about money. $5 million was given to rebuild the streets but only $1.5 million was used. What happened to the rest of that money?” asked McCloud.

“They want this because everyone makes money off of this— jails, the city, everyone,” said McCloud.

Before gentrification first occurred downtown, “the city’s waterfront was turned into a wasteland of rotting piers, railroad tracks, abandoned factories and warehouses. Its isolation and deterioration took on an eerie quality and it became a place for youths to seek adventure and engaged in mischief,” described Malone in his article, “Jersey City: Lessons from Unequal Development.”

“We recognize the signs [of gentrification],” the Reverend Elliot said.

“Now we have a change in strategy,” she said.

What long-time residents weren’t prepared for was the attention of the Orthodox Jewish community in the Greeneville area.

Many residents’ feel that instead of creating affordable housing people are being displaced completely. Many fear that the Greenville community will become a new neighborhood entirely, as there have been harassment complaints from homeowners.

“They knock on people doors and lie about the value of the property,” said Johnson.

The chassidishe Jewish community said that they want to live in the Greenville area because New York has become unaffordable particularly the Crown Heights area of Brooklyn. Chassidishe families who are low income can no longer afford to live there. Jersey City is an up and coming community, with affordable houses, and a short commute back to Brooklyn.

When asked of the Orthodox Jewish communities’ interest in Greeneville, Mayor Fulop was hopeful, saying that Jews and Blacks can live peacefully together. But many residents are alarmed at the interest because Orthodox Jewish communities are known for being insular. Many residents believe that they are trying to take over the community.

In response to the concern of displacing the long-time residents, the orthodox Jewish said that they aren’t trying displace the people.

However, in the Jewish newspaper 5 Towns Jewish Times, in an article written by Rabbi Gershon Tannenbaum, titled, “Greenville, Jersey City: A New Chassidishe Community,” Tannenbaum states, “In spite of the geographic desirability, the housing stock is cheap. A most recent listing of homes available in Greenville has a 9-bedroom, 6-bathroom home for $549,000; an 8-bedroom, 3 bathroom home for $328,000; and a 3-bedroom, 2 bathroom home for $325,000, amongst many other similar offerings.”

Tannenbaum continues, stating, “Several chassidishe philanthropists have joined with real estate investors to transform Greenville into a chassidishe community with ample affordable housing—with the beginnings of Greenville’s chassidishe community now firmly established, the directors of the Ya’azoru Project will begin a campaign of outreach to every chassidishe kehillah (a Jewish community with shared interest) with an invitation for them to establish satellite communities and institutions in the new chassidishe Greenville.”

It has been reported that 11 Orthodox Jewish families have already moved into the community and 50 to 60 properties are under contract.

Another reason residents are skeptical about the Hasidic community coming to the city is the history of the Orthodox Jewish completely inhabiting Brooklyn.

Residents criticize, that while many are being displaced in large numbers due to the lack of affordable housing, the housing the Chassidishe community has created has not been extended to any non-chassidishe residents; especially those who could benefit from low-income housing. Instead, residents complain that they are only offering low-income to other orthodox Jews. One resident even noted that their flyers for low-income housing is only written in Hebrew and published in Jewish publications.

Displacement has happened in Jersey City before and is happening at the moment in large numbers, however.

Many homeless and low-income families are being uprooted from their communities because there weren’t any homeless shelters left in the city. To accommodate, the county’s decision was to send the homeless to Newark’s, YMCA. The city screamed with outrage of this injustice, as they called it.

“What a travesty to send your people who were born and raised here and tell them that you have to go to the YMCA in Newark,” said Johnson.

“My sister was laid off and lost her home. Now she and her daughter are in a homeless shelter,” said Johnson.

Lissette Martinez, member of Love of Jesus Christian Family Church, a guest speaker of the town meeting, and mother of three, discussed the conditions of the Starlight Motel, which was the last temporary housing for the homeless. She described all, from the rodent infestation to the bedbug squalor. She discussed the neglect and the second class treatment from the hotel’s staff. Rodriguez explained that the microwaves were removed from all of the rooms of the displaced, so she was not able to feed her children warm food the six months they lived in the motel.

“The Starlight Motel was given $33 per person, per night. That is $5,000 per month,” said Martinez.

Martinez explained that due to the appalling conditions of the motel, they were shut down, yet when it was time for her to look for housing she was sent to Newark, New Jersey, because the county said that there was nothing available in Jersey City.

Reverend Jessica Lambert, of St. Paula’s Lutheran Church, took her place at the right side of the alter, directing questions to DeGise, he asked for accountability for the homeless conditions $3 million per year to go toward the Hudson County Homeless Trust Fund and for 85-150 affordable units developed every year.

DeGise, standing on the left, retorted, “I don’t collect taxes the way the mayor does.”

DeGise said that he could not commit to the proposal of $3 million a year.

“Some are being squeezed out of Jersey City altogether. There’s simply not enough room for the poor,” said Lambert.

“[Other low-income] families are being forced to decide between paying ever rising rent and feeding children,” said Reverend Lambert.

“[That’s] what happens when middle class are buying up property—where are they [poorer residents] going to go, the path of less resistance. They always travel the road of least resistance. They move wherever they can afford to move, in whichever neighborhood has cheaper rent. There are entire cities that become unaffordable—Brooklyn, Manhattan, San Francisco,” Herman says.

“[In this case] it’s the spillover effects of NYC real estate market,” said Herman.

“[Now there are] cultural and economic clashes as the city transforms,” stated Herman.

“[Except this] sends a negative message to the people in the city—when some neighborhoods receive the bulk of resources and other neighborhoods are not receiving any resources aside from police,” Herman says.

One of the greatest disparities is treatment of crime in downtown compared to Greenville.

Herman explained that the purpose is to contain the crime—to maintain the violence in the poorer and minority based neighborhoods to avoid it spilling out in wealthier and whiter areas, with those how have more voice and power and will fight back.

Johnson explains that Mayor Fulop has not taken accountability for lack of action in black neighborhoods.

“He is the first mayor who addressed crime on Facebook,” said Johnson.

“You can’t report numbers when it comes to crime when it doesn’t get reported— shootings occur every night,” stated Johnson.

“The community won’t be witnesses to what’s going on. There’s a lack of trust between the police and the community,” Johnson stated.

“ [Fulop] said that the cause of all of the violence was because of the conflict between two groups of ten people. The number continues to increase. You mean to tell me they never caught the first 10 people,” said Johnson.

“Fulop said that he hired 100 new police officers. They were divided up between the wards and the largest two wards A and F were only given 37 new officers. 15 of the officers were rookies teams with veterans. These wards have the highest rates of violence in the city. We don’t just want to see them but we need them,” said Johnson.

“Individuals are becoming more brazen,” said Johnson.

“Yvonne just happened to be walking out of a store when she was shot in the stomach at 2:55pm on a weekday. At 1 p.m. there was police presence they were gone by 2:55 pm,” said Johnson.

“Larry Freeman lost his life by the same gunman,” said Johnson.

“The three different people were shot in one day,” said Johnson.

“The heart of the city is in Ward A and F. There’s pain this this community but also a lot of love,” said Johnson.

“Downtown is protected—Darren “Reese” Talington was trying to protect a woman and was shot. The store that he was killed in front of [called A-Plus Deli] was located downtown and was shut down after 20 years of business,” said Johnson.

“Davonte Carswell was killed inside of the basement of a bodega [called Los Yolersos Mini Market], his body was moved to conceal the gambling spot in the basement—[yet] the store was closed for six weeks and re-opened under a new name,” continued Johnson.

“There’s no value of black lives. That store was the only late nightspot— so everyone went there—[but] they don’t want a negative reputation. When the violence moves downtown they will close the store,” said Johnson.

“We are portrayed as a race to be feared, but I feel safer in my community than in white communities,” said Johnson.

Deacon Lawrence Alexander of New Hope Missionary Baptist Church, stated, “We need to build better relationships between the police and communities.”

He developed two proposals, which was the immediate allocation of $400,000 to repair cameras in the south district. And a commitment to get the rest running in the south and the west, street policing until at least the end of the summer, and build relationships because just walking is not enough.”

Fulop returned to the left side of the stage and said that he inherited a faulty system. He said that he was committed to hiring 900 police officers, having walking posts in the south district, but that the city needs an academy. He walked away.

After urging the mayor to return to his position, the speaker asked why the CCTVs (camera) weren’t working in the highest crime district.

Fulop resumed his position, repeating that he had a plan but the problems was “inherited,” they “working through” it, “repairing,” but that he cannot commit to the proposal.

“It’s all smoking mirrors, Fulop has to come across like he’s made an impact in Jersey City to successfully become governor. That’s not factual,” explained Johnson.

“All Fulop has to do is to point how the image of the city has improved, —[and that] prior to the [developments] Jersey City was a postindustrial city with minimum wage jobs, it was a run down postindustrial city,” said Herman.