NJCU Canvasses in Georgia

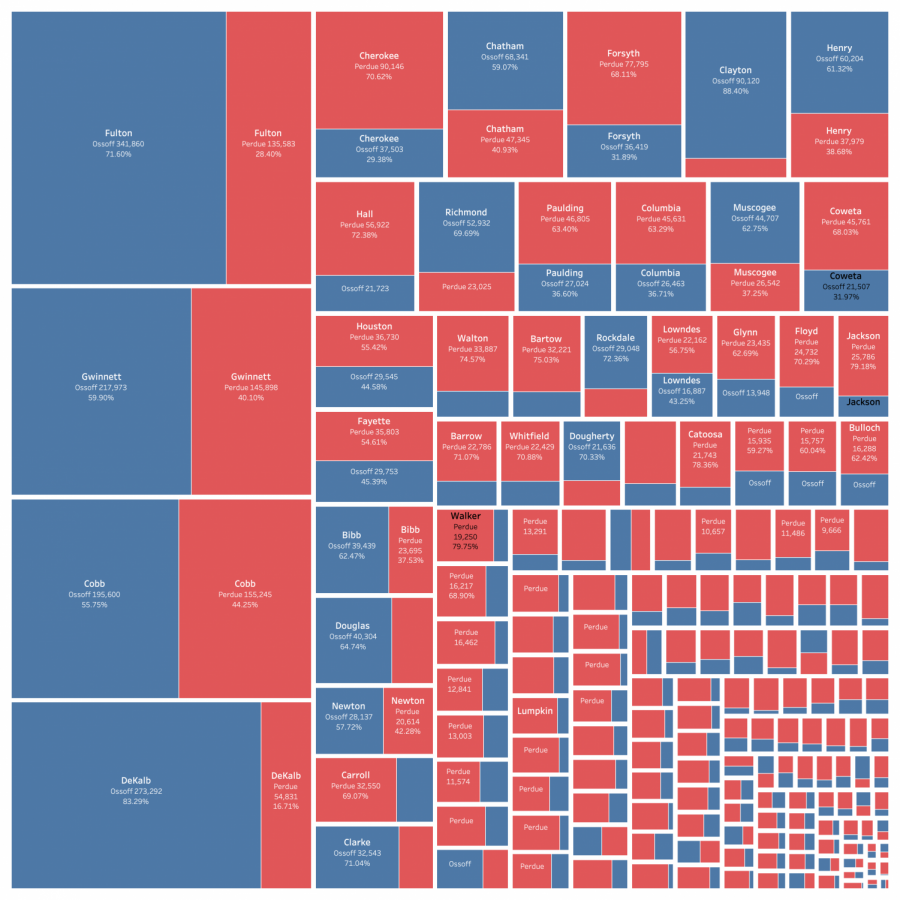

Georgia runoff election results by county. Photo by Dennis Bratland/ Wikimedia Commons. Zoom in to see percentage results.

January 21, 2021

When Georgia “turned blue” and voted in two Democratic senators in the January 5 runoff, it wasn’t that citizens had simply changed their minds about who to vote for.

Stacey Abrams and thousands of other Georgian activists have shown that the real change came from fighting the many decades’ suppression of Black people’s and young people’s votes – those most likely to vote Democratic. Suppression takes many forms: state and county officials closed polling sites or moved them to hard-to-reach places; new rules made it harder to vote and easier to reject ballots.

I recently retired after 25 years of teaching in the English Department at NJCU. In December 2020, I drove South to escape winter while staying out of planes. My wife and a friend stopped in Savannah, Georgia for a few days to help Democrats reclaim or “cure” blocked votes. We went door to door visiting voters whose mail-in ballots had been rejected, to help make sure that their votes would count. Georgia Democrats Ballot Rescue Canvassing gave us lists, instructions, and apps to work with. We learned what error the voter committed when they sent in their absentee ballot. The registrar said their signature didn’t match their ID, they hadn’t checked off the unnecessary but required box that said the ballot was for the Jan. 5 election, or something else that seemed meant to trip them up. Some voters had received the notice that they had their vote denied while others had not. It was shocking to see up close how much effort people had made to vote, and then had their votes batted away.

We also spoke to a veteran in his 50s in a wheelchair who had become disabled since signing his ID card. He now could only make an X for his mark, which didn’t match his old signature. His mother had helped him fill out a paper affidavit and sign it with his X. The next steps were hard to complete without a cell phone or computer, or the time to drive to the registrar’s office. We helped them get it to the registrar immediately using my cell phone. This veteran, who needed to vote by mail because of his disability, and had sent in his ballot, had essentially been told that his disability could take away his vote.

Our list included student housing at the Georgia Southern University, where students were still away on break and didn’t know their votes were blocked. Other students promised to reach out to their roommates to cure their ballots. We left literature on the doors of people we didn’t speak to, to explain what objection the county registrar had raised, and how to fix it.

Each visit was a small drop in the effort. Georgians who had been disenfranchised before believed their votes could do something had the courage to rise to uphold that belief, and voted. It took thousands of volunteers’ work calling and visiting voters to begin to undo the state of Georgia’s efforts to block votes.

For more information about Stacey Abrams and the Democratic canvassing in Georgia, visit https://fairfight.com/