What Happens When We Don’t See Ourselves?

The Reality of Black Women on Screen

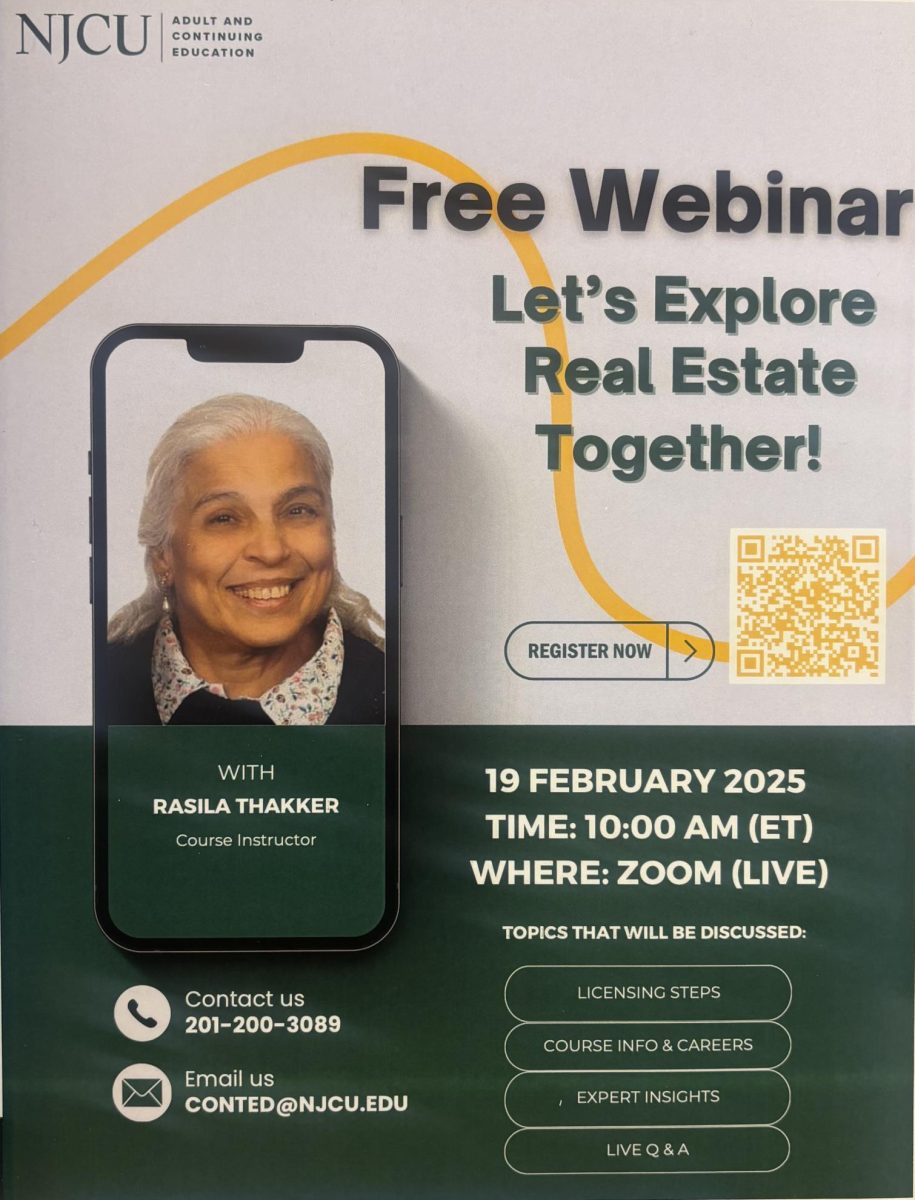

ABC Signature Studios [Fair Use]

Costars Yara Shahidi (biracial) and Trevor Jackson (monoracial) act out a conversation during recent season of hit TV show Grown-ish. Photo Courtesy of ABC Signature Studios [Fair Use]

November 4, 2021

While roles for Black women in modern television and film have expanded, much could be improved.

Numerous shows now provide multiple Black main characters and dynamic supporting roles. A generation of young Black girls will look up to these characters, for example in Grown-ish, Grey’s Anatomy, and Euphoria.

Yet many of these leading characters are portrayed by biracial or racially ambiguous actresses with lighter skin tones, loose curls, smaller nose bridges, and other characteristics often praised by mainstream society.

These features also happen to be the same traits that are used to make young Black girls feel undeserving, as they are given the message from multiple outlets, particularly modern media, that they are the less wanted version of Black femininity and should strive to look more like the light-skinned females who are painted as the ideal.

In other words, the media seems to almost always select girls who appear to be racially mixed, as if the features of a mono-racial Black character are not desirable enough. They do this regardless of whether the character is mixed as seen by the portrayal of Star Carter by Amandla Stenberg in the popular 2018 movie The Hate U Give.

In the novel that the movie is based on, Star is described as a dark-skinned girl with a puffy afro. Why then did the directors cast a mixed girl with much lighter skin to play her, especially in a movie so important to the plight of Black teenagers in America?

Most Common Stigmas in the Media

In the past, there has been an insultingly low number of Black female leads, and they were almost always portrayed unfairly as unnecessarily loud, impolite, and unappealing as compared to girls of other races in the same show.

Black students are familiar with the depiction of the dark-skinned Black girl with an impossible attitude and crass behavior or the intentionally less attractive side character who is cast only to be the white main character’s rock of support or comic relief.

These tropes may not always be noticed by other races and are especially overlooked by the white majority that is most accustomed to accurate and multi-faceted representation in media. In the Disney shows K.C. Undercover and Bunk’d, we see Black characters like Judy and Zuri who display exaggerated sassiness, amid several other racial stereotypes.

Self-Esteem and the Modern Black Woman

Colorism is the assertion that people of lighter skin tones are more attractive or somehow more deserving than those of darker skin tones commonly involving nose shapes and hair texture. This bothers me as I am a dark-skinned, kinky-haired Black woman bombarded by a ceaseless stream of slander from multiple sources centered around my hair texture and skin tone.

Even among my friends, I felt as if I had no choice but to shrug off hate-charged comments about darker Black girls being difficult in friendships and relationships, wearing extensions or chemically straightening because we must have secretly hated our natural hair or other myths that ranged from being random to outrageously untrue.

I would go to school and hear these awful statements about people who looked like me spoken by my peers, only to go home and see almost no examples of Black women with my features in music, television, or literature to prove these people wrong.

As a result, for multiple years, I resigned myself to assuming these stories were realistic, as there was so little to remind Black female youth of their versatility, good-heartedness, brainpower, and physical desirability.

This is the cause of a large portion of self-hate, confusion, and identity crises Black females face during childhood, which normally pours into the teenage years or adulthood. It’s simultaneously unnecessary, painful, and unfair. It is a vicious mindset that can take a frighteningly long time to rectify.

Such accounts are the reason why it is dangerous that in mass media, traits that are centered around whiteness are endlessly praised.

So, what can we do about colorism in casting for television shows? We can make more of an effort to put Black females with other, less fetishized features in the media. Black creators should be uplifted to promote genuine representations of Black people. When Black characters are cast, we can advocate for upcoming actresses with darker skin, larger lips, and kinkier hair, especially those who are mono-racial.

If their casting choices are harming the mindsets of generations of Black youth and planting seeds of doubt and deceitful stereotypes in their heads and hearts, then their faulty representation matters and must be addressed. These movies and films affect not only how the rest of the world perceives Black characters, but how Black people perceive themselves. As a diverse community of media consumers, we have to refuse to let them continue to create this narrative by calling them out for their damaging actions.

![Costars Yara Shahidi (biracial) and Trevor Jackson (monoracial) act out a conversation during recent season of hit TV show Grown-ish. Photo Courtesy of ABC Signature Studios [Fair Use]](https://gothictimes.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/6.1-Grown-ish-1-900x600.jpg)