On July 16, 1945, the world’s first nuclear explosion occurred, tested south of Los Alamos, New Mexico, at the plains of the Alamogordo Bombing Range. It boasted an implosion-design plutonium bomb, invented by J. Robert Oppenheimer, and would later be used again for the Little Boy, the bomb that would detonate over Hiroshima on Japan, on August 9, 1945, during World War II. An estimated 150 to 246 thousand people were killed, and this moment remained the one of two uses of nuclear weapons in armed conflict. It is by far one of the most horrific, and violent display of weaponry, and still echoes throughout time. It’s a ripple that has reached modern day America and Japan, and doesn’t deserve to be forgotten, as contemporary artists has made sure of that.

The latest exhibit has hit NJCU, and this time, it’s a double feature with two different curators showing off this collection.

The Atomic Cowboy: The Daze After/Take It Home, for ( ) Shall Not Repeat the Error commemorates the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, with numerous pieces of different artists coming in to showcase their art, of which sends a message about the nuclear testing and bombs that devasted many.

Despite being over 80 years, it has become more important now than ever we don’t forget these events.

Take It Home, for ( ) Shall Not Repeat the Error, curated by Souya Handa, features artworks by four contemporary artists, all of which expressing the terror, and power of the bombing on Hiroshima and the like. Nuclear tests like Trinity often appeared in these works, along with other and an expose on the U.S.’s use of nuclear bombs, featuring artists based in Tokyo, Congo, and Baltimore.

Handa’s “Time is Moving But the Clock is (Glazed)” is an ominous piece, with an LCD piece that displays the time for August 6th, 8:15 AM, the time of the original atomic bomb that exploded on Hiroshima. Its chain fence that holds up the piece can be traced back to the gates that would warden off people from entering these dangerous sites. The melted glass it is put upon is reminiscent of the intense heat of the nuclear bomb. It is a glimpse into the destructive power that the original bomb had, and the aftermath of Hiroshima after its destruction.

Handa has stated that his inspiration for this piece comes from the museums he often visited as a child, which showcased the Hiroshima bombing, and used the LCD to show the ambivalent feeling of time. As he states “I have been to the museum several times from my childhood to adulthood…We are still working, but at the same time, we are still holding the stopped clock.”

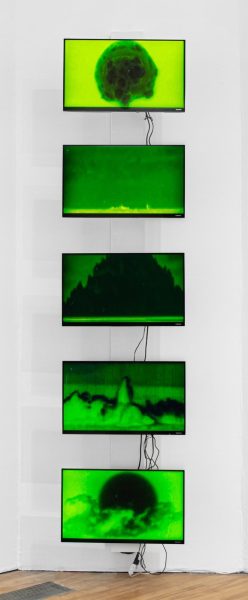

Another piece shown in Take It Home was Kei Ito’s “Aborning New Light,” a video installation with greenish videos, of which are sourced from the archival footage of American Nuclear testing. These films were rescanned from exposed, light-sensitive paper into a single film.

The main feature of this work is the use of sunlight to create these altered images, a staple of Kei Ito’s process in many of his work. The prominent use of sunlight can be traced back to Ito’s grandfather’s trauma, who had lived through the Hiroshima incident, and describes the moment of the bombing as “hundreds of suns lighting up the sky.”

Another interesting aspect of this piece was the use of Godzilla figurines or Enola Gay Toys, both of connected to nuclear bombs.

The most peculiar aspect is how the video is in reverse, which as Ito has stated in her website, helps to give the feeling that “time counts down to a period before nuclear weapons and their extreme proliferation across the globe.

Another of Ito’s work was called “Burning Away.” This piece was a long-term project by Ito, using honey and various oils on a sun-infused paper to create the image. Although being an odd choice, honey has major significance in the piece’s creation, as it was used as a remedy to treat the burns that were inflicted by the searing light of the bombings, along with cooking and motor oil.

The reason why they relied on these substances were due to the scarcity of base medicine at the time. This piece seeks to recreate that memory of that nuclear fire, and the healing that many survivors went on, hoping to get past the trauma of the event. In a way, it is preserved in honey and sunlight.

Atomic Cowboy: The Daze After was also featured in the exhibit alongside Souya’s Exhibit, by Nobuho Nagasawa. It was based on the actors and Native Americans that were affected by the radiation in the film sites, which were near nuclear testing grounds.

Its central feature was the “Nuke-Cuisine,” a tower of 91 soup cans, all fashioned with pictures of the mushroom cloud emitted by the bombing. It originally had 835 cans stacked together, however due to the limited space of the Visual Arts Gallery Room, it was toned down to 91.

It originally hosted 835, since that was the number of the “announced” nuclear test, conducted between 1945 to 1992. The cans also have ingredients on their sides, which shows what goes into the creation of nukes.

When the exhibit was first showcased in its original location, it received a lot of backlash by people involved in the original nuclear tests, and Nagasawa received a lot of hatemail for being Japanese and talking about it, despite merely wanting to spread awareness.

Other things that appeared in this exhibit during the first showcase were the nuked cookies of humanity, which were shaped after the soldiers who were affected by the nuclear tests. In case you were wondering, yes, you could eat them.

All in all, these exhibitions were brought together by Prof. Midori Yoshimoto to raise awareness on nuclear weapons and the threat they bring. Despite nukes never being used again in warfare, that does not mean that the threat of a nuclear war is not gone. Ever since it was created, everyone knew that a blueprint for utter destruction existed, and many sought after it. There are numerous nuclear weapons owned by many countries around the world today, and in these tense times, it has become paramount that we never forget what happened 80 years ago.